WARSAW, Poland (AP) — In the early months of 2022, as Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine began, millions of Ukrainians — mostly women and children — fled to Poland, where they were met with an extraordinary outpouring of sympathy. Ukrainian flags appeared in windows. Polish volunteers rushed to the border with food, diapers, SIM cards. Some opened their homes to complete strangers.

In the face of calamity, Poland became not just a logistical lifeline for Ukraine, but a paragon of human solidarity.

Three years later, Poland remains one of Ukraine’s staunchest allies — a hub for Western arms deliveries and a vocal defender of Kyiv’s interests. But at home, the tone toward Ukrainians has shifted.

Nearly a million Ukrainian refugees remain in Poland, with roughly 2 million Ukrainian citizens overall in the nation of 38 million people. Many of them arrived before the war as economic migrants.

As Poland heads into a presidential election on May 18, with a second round expected June 1, the growing fatigue with helping Ukrainians has become so noticeable that some of the candidates have judged that they can win more votes by vowing less help for Ukrainians.

“The mood of Polish society has changed towards Ukrainian war refugees,” said Piotr Długosz, a professor of sociology at the Jagiellonian University in Krakow who has carried out research on the views toward Ukrainians across central Europe.

He cited a survey by the Public Opinion Research Center in Warsaw that showed support for helping Ukrainians falling from 94% at the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion in February 2022 to 57% in December 2024.

“Many other studies confirm the change in mood,” he said. “At the same time, it should be remembered that helping refugees after the outbreak of the war was a natural moral reflex, that one should help a neighbor in need. All the more so because Poles remember the crimes committed by Russians against Poles during and after two world wars.”

Candidates adjust to anti-Ukrainian sentiment

Among those to transform the shift in mood into campaign politics is conservative candidate Karol Nawrocki, a historian and head of the Institute of National Remembrance who is the Law and Justice party’s chosen candidate and one of the frontrunners.

Law and Justice, still in government in 2022, led the humanitarian response to the crisis along with President Andrzej Duda, a conservative backed by the party who traveled to Kyiv during the war.

As Nawrocki seeks to succeed Duda, he is showing ambivalence toward Ukrainians, stressing the need to defend Polish interests above all else.

Duda and Law and Justice have long admired Donald Trump, and Nawrocki — who was welcomed at the White House by Trump on May 1 — has at times used language that echoes the American president’s.

“Ukraine does not treat us as a partner. It behaves in an indecent and ungrateful way in many respects,” Nawrocki said in January.

After Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s tense visit to the Oval Office in February, Nawrocki declared the Ukrainian leader needed to “rethink” his behavior toward allies.

Last month Nawrocki vowed that if he wins, he will introduce legislation that would prioritize Polish citizens over Ukrainians when there are waits for medical services or schools.

“Polish citizens must have priority,” Nawrocki said in a campaign video. “Poland first. Poles first.”

Further to the right, candidate Sławomir Mentzen and his Confederation party have gone beyond that. He has blamed Ukrainians for overburdened schools, inflated housing prices, and accusing them of taking advantage of Polish generosity.

At an April 30 rally of a far-right candidate, Grzegorz Braun, his supporters climbed up to a balcony on city hall in Biała Podlaska and pulled down a Ukrainian flag that had been hanging there since February 2022 as an expression of solidarity.

The political center is adjusting too.

Rafał Trzaskowski, the liberal-minded mayor of Warsaw from Prime Minister Donald Tusk’s centrist party who welcomed Ukrainians to his city in 2022, proposed in January that only Ukrainian refugees who “work, live and pay taxes” in Poland be granted access to the popular “800+” child benefit — 800 zlotys ($210) per month per child.

The requirements were already tightened recently, and some refugee advocates described it as a concession to far-right narratives.

Ukrainians say they’re helping Poland, too

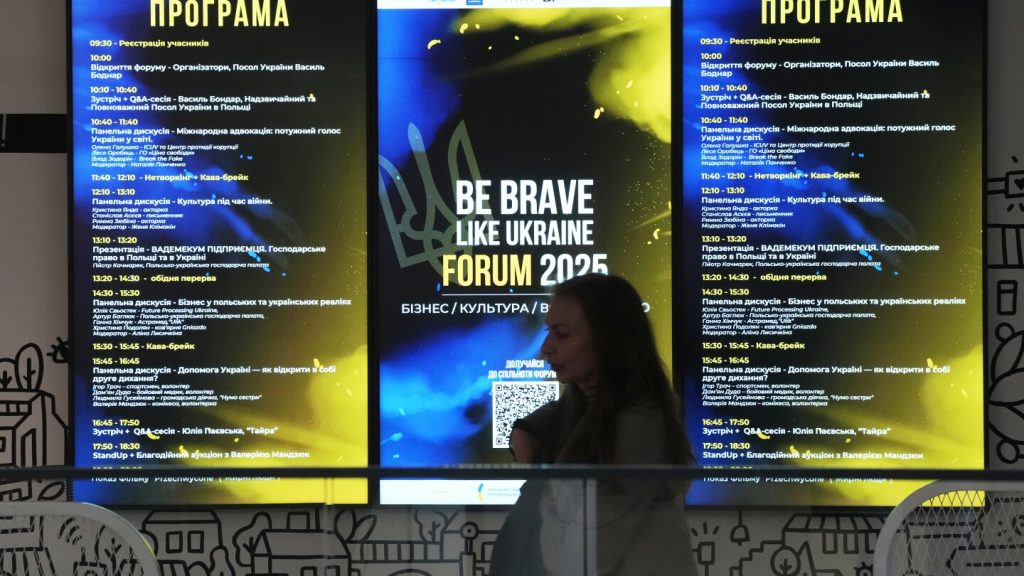

Ukrainian Ambassador to Poland Vasyl Bodnar disputes claims that Ukrainians are taking more than they give. About 35,000 receive support without working, he said, but what they receive is only a fraction of what Ukrainians contribute in taxes. He noted that some 70,000 Ukrainian-run businesses now operate in Poland.

“Ukrainians are helping the Polish economy to develop,” he told The Associated Press.

Małgorzata Bonikowska, president of the Center for International Relations, said that it is normal for tensions to emerge when large numbers of people from different cultures suddenly live and work side-by-side. And Poles, she added, often find Ukrainians pushy or entitled, and that rubs them the wrong way. “But there is still very stable support for helping Ukraine. We truly believe Ukrainians are Europeans, they are like our brothers.”

Rafal Pankowski, a sociologist who heads Never Again, a group that fights xenophobia, has tracked anti-Ukrainian sentiment from the start of the full-scale war. At first, the far right was very isolated in its anti-Ukrainian opinions, he said.

“What is happening this year is harvest time for all those anti-Ukrainian propagandists, and now it goes beyond the far right,” he said.

Kateryna, a 33-year-old Ukrainian who has lived in Poland for years, has seen the change up close. In 2022, strangers often greeted her with sympathetic looks and with the words “Slava Ukraini” (Glory to Ukraine).

But then last fall, a man on a tram cursed her for reading a Ukrainian book. This spring, outside a social security office, another man shoved her and screamed, “No one wants you here.”

She asked that her last name not be used because she works as a manager in a company that would require to have clearance to be identified publicly.

Her parents remain in Ukraine, and her brother serves in the army. Like many in the region, she believes Ukrainian resistance is keeping Poland safe by holding the Russians at bay.

Tensions now, she worries, only serve Moscow. “We must stick together,” she said.