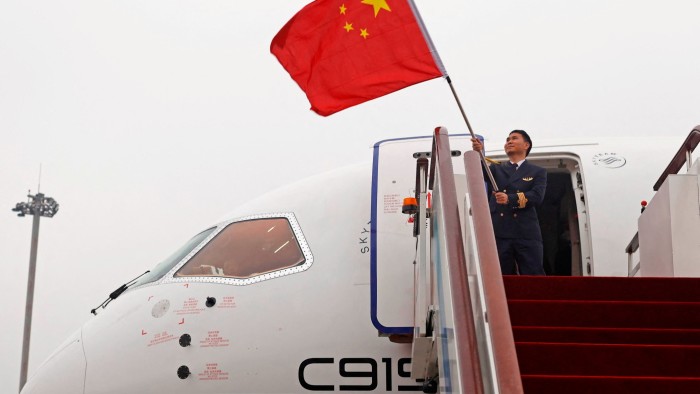

For years, Beijing has had high hopes that Comac’s C919, China’s first domestically made airliner, could challenge the aircraft market dominance of Boeing and Airbus, showing China’s technological self-reliance and the advances made by its state-run plane maker.

But as the US-China trade war escalates, analysts are warning that the C919’s heavy reliance on US suppliers for critical components could threaten plans to increase production and even hit the maintenance of passenger jets already in operation.

With China’s three big state-owned airlines already flying 17 C919s and Comac expecting to build at least 30 more of the single-aisle aircraft this year, the tensions between Washington and Beijing are highlighting how Chinese companies can be heavily dependent on US companies in their supply chains.

The C919, which made its maiden commercial flight in China in 2023, has 48 major suppliers from the US, 26 from Europe and 14 from China, according to Bank of America analyst Ron Epstein.

For most western aircraft components for the jet, there are no domestic alternatives readily available, analysts say, meaning the US “can [halt] Comac in its tracks anytime it wants”, said Richard Aboulafia, managing director of AeroDynamic Advisory.

One of the most crucial parts of the C919, its LEAP-1C engine, is built by CFM International, a joint venture between the US group GE Aerospace and French manufacturer Safran. While China has been developing a domestic alternative, the CJ-1000A, it is still being tested and is “not ready yet”, said Dan Taylor, head of consulting at aviation consultancy IBA.

While CFM International continues to build the engines, including in France, added Taylor, the core module is produced in Ohio. “If access to that was interrupted, it could become a major headache for Comac,” he said.

Other US suppliers for the C919 include Honeywell, Collins Aerospace, Crane Aerospace & Electronics and Parker Aerospace for various critical components and aviation systems. Honeywell did not respond to a request for comment, while Collins declined to comment specifically on its relationship with Comac.

“Unlike many other industries, the commercial aerospace industry did not become dependent on low-cost manufacturing in China,” BofA’s Epstein wrote in a note. “Most Chinese suppliers on the C919 are . . . not high value-add subsystems such as engines, controls, avionics or actuation.”

Sash Tusa, a UK-based aerospace and defence analyst, said that while the US “has not [yet] said they will not supply [components for the C919] — that may be the next stage”. Ongoing after-market services, including repair and maintenance support of C919 jets already in operation, will also have to rely on US suppliers, aviation analysts say.

For now, it is “likely that Comac has enough inventory to cover near-term deliveries”, IBA said. China has also already granted some tariff exemptions on US imports, including several aviation-related products. Safran said last week that China granted tariff exemptions for imports of certain aerospace parts.

But if the US, at some point, decides to restrict exports of key components to China and “if China stops buying aircraft components from the US, the C919 programme is halted or dead”, Epstein said.

Comac has been studying the effects of the tariff increases and sales have “not been impacted”, according to one person close to the company. The aircraft manufacturer did not respond to a request for comment.

China’s state-run airlines would be worst-affected if US-China tensions derailed Comac’s production capabilities. By 2031, Air China, China Eastern and China Southern Airlines are each expected to operate fleets of at least 100 C919 aircraft, according to Mayur Patel, head of Asia for OAG Aviation.

But Comac only delivered 13 C919s last year to Chinese airlines, and aviation consultancy Cirium Ascend said only one C919 was delivered in the first three months of this year.

Recommended

Analysts say Comac’s slow production rate means its aircraft cannot be Boeing or Airbus replacements for the foreseeable future. Beijing appeared to recognise this reality on Tuesday last week, with the commerce ministry saying China was willing to support normal co-operation with US companies, only days after Chinese airlines rejected taking delivery of any new jets from Boeing.

The tariffs and uncertainties around western supplies of critical components could also prompt Comac to rethink its priorities to deliver and fly the C919 beyond China.

The airliner still lacks international certification, including from the US’s Federal Aviation Administration and from Europe’s aviation regulator, which limits Cormac’s ability to fly outside China and its efforts to boost global sales. The European Union Aviation Safety Agency recently said it would take three to six years for the C919 to gain approval.

But according to aerospace analyst Tusa, access to overseas markets may not be a significant issue for the C919. “As long as it supplies a large proportion of the Chinese domestic market, that is good demand in and of itself,” he said.

Additional reporting by Claire Bushey in Chicago